Feeding Picky School-Aged Kids

And why their pickiness probably isn’t your fault.

"Eat a varied diet while you're pregnant," they said.

"Eat many different foods when nursing because the flavors come through in your milk," they added.

"Expose your kids to lots of new tastes within the first two years of life," they preached.

"Take them to the farmers' markets. Grow food and invite them to join in."

This…is how "experts" tell you to avoid having the dreaded picky eater.

And for a while, it all worked.

"She loves broccoli rabe. We'll keep her!" I declared on Facebook when my eighteen- month-old happily chomped down a stalk. A friend tried to warn me that her openness to new foods might not last long, but I didn't listen.

My daughter was born in 2012, the year of Pamela Druckerman's Bringing Up Bébé and French Kids Eat Everything by Karen Le Billon. Both of their books insist that kids in France, in general, aren't picky because they're taught the pleasures of the table from an early age, and their parents expect them to eat a variety of foods.

I can do that, I thought.

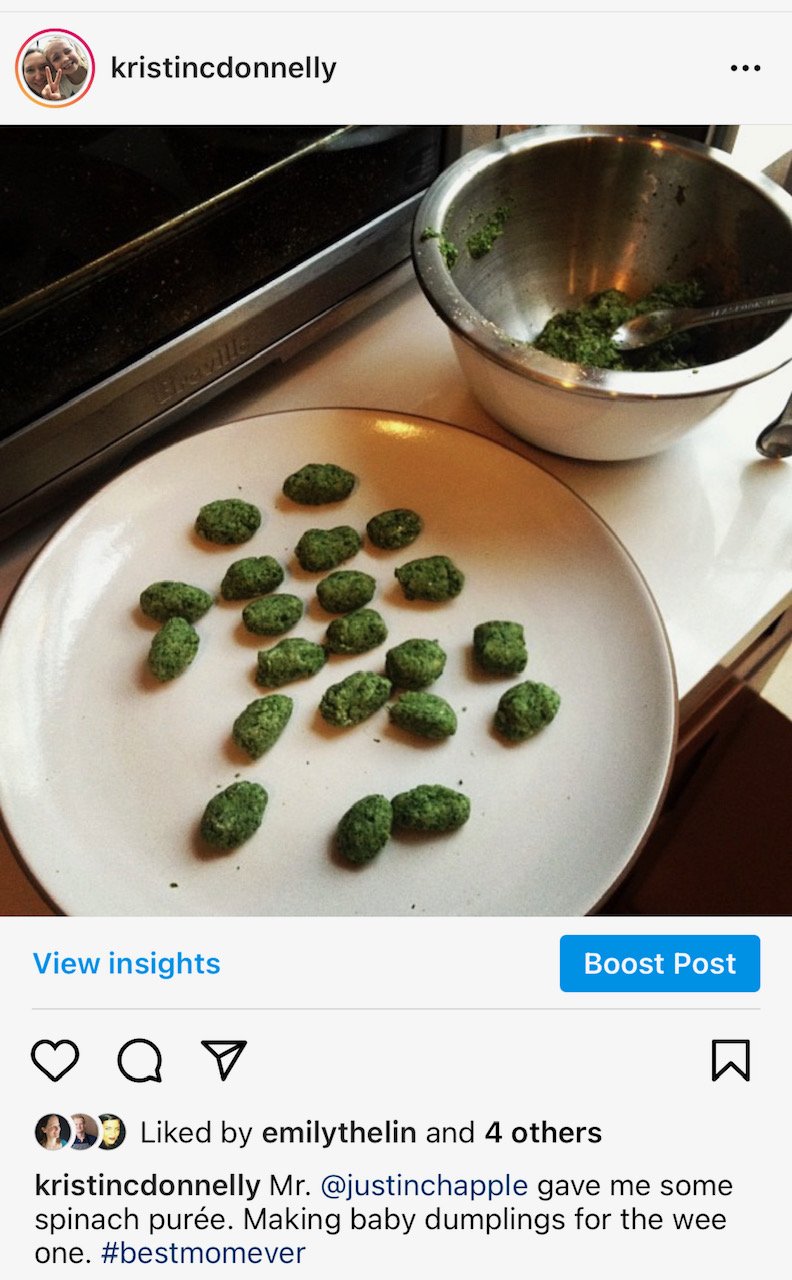

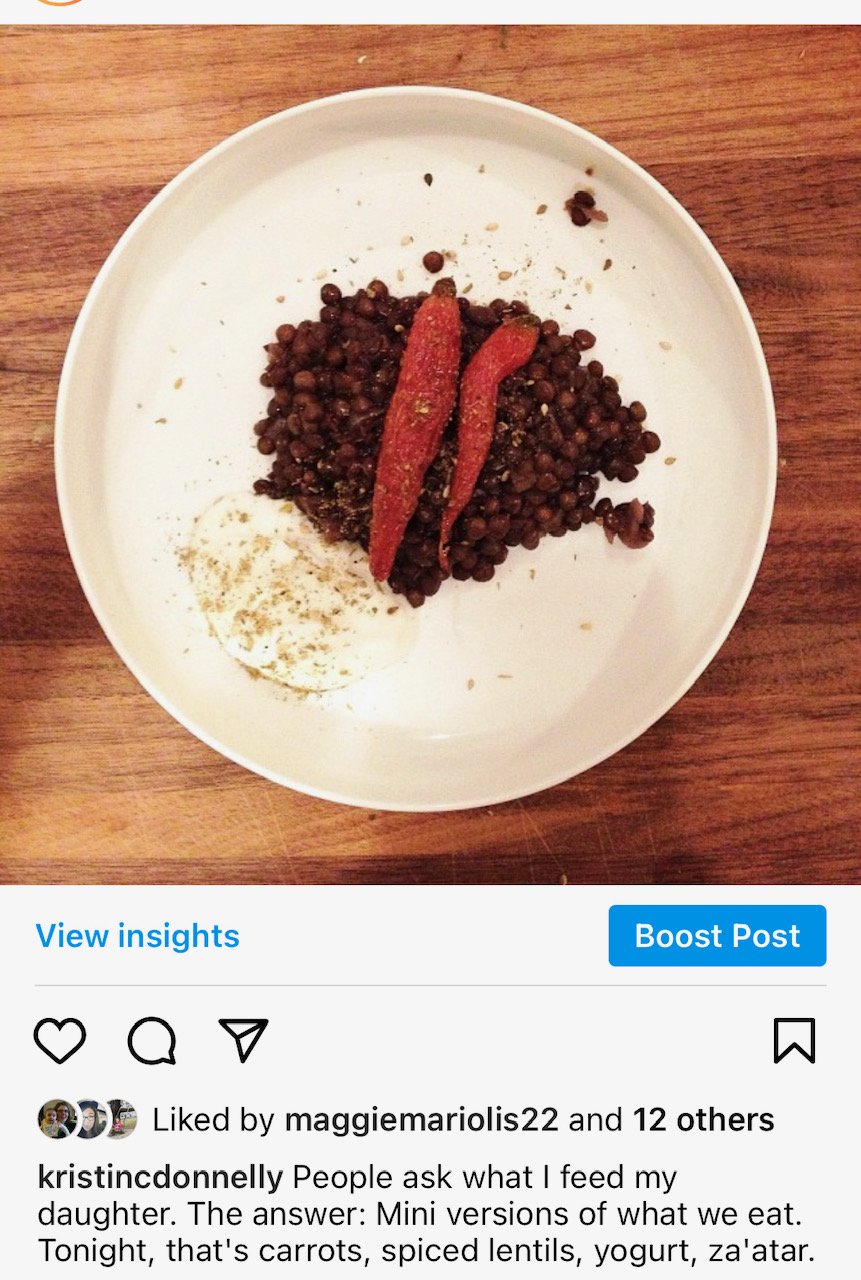

As a baby, she happily slurped down all of my homemade purees: roasted fennel with parsnip and apple; peas with coconut milk; broccoli with chicken.

I would coo to her about the delicious flavors of each, imagining her future as a precocious child telling a restaurant server, "I don't need the kid's menu."

When she was a bit older, I brought out the knife skills I hadn't used since culinary school and cut sweet potatoes and parsnips into small dice to roast so she could enjoy them while practicing her pincer grasp.

In preschool, she ate home-packed lunches of lentil soup with sausage or rice and beans, or roasted chicken with vegetables.

And dinner was always some version of what we ate. Unless we went out to restaurants, that is, and then we gave her food from our plates. (I remember a time when she couldn't get enough of the clams and mussels my husband ordered once.)

Please don’t judge this Instagram photography circa 2014.

Until about age five, we continued along this path. She ate what I prepared with minimal complaints and enjoyed some sweets and the occasional junky snack. Ok, sometimes, a bit of bribery was involved. Eat this dinner, and you can have this sweet. But she never utterly refused food.

I didn't realize that to maintain this ideal (in my mind) way of eating, I'd need reinforcement from everyone else around me, especially as she got toward school age.

Damn you, school lunches!

My internal alarm bells started going off when she first bought lunch in kindergarten. She told me she ate mac & cheese, a roll, sugary yogurt, applesauce, milk, and Cheetos.

Just typing this makes my mildly lactose intolerant stomach churn. (The Cheetos, I found out later, were not part of the typical school lunch but offered as snacks kids could purchase. Ugh!)

Now I know Michelle Obama worked with the best intentions to improve school lunches, at least from a health and wellness point of view. She helped Congress pass new standards for the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), so school meals would have fewer calories, more fruits and vegetables, fewer processed items, and less sodium.

But flavor and quality of the food (including the produce) were ultimately not a factor in the legislation passed. And some of the regulations are misguided and based on old science. (Low-fat and non-fat dairy is not only a travesty of flavor but less satiating, so kids end up eating more sugar and refined starch.)

When you ask schools why they don't provide more varied options or insist kids take fruits and vegetables, they say kids don't eat them so they just go to waste. Also, most schools are set up to warm food, not cook it from scratch, so the fruit and vegetables are often canned or frozen. When fresh, they're usually not the tastiest versions of themselves. Who can blame kids for skipping them?

So now we're left with a self-perpetuating cycle: Kids refuse "healthy" food, so we don't serve it to them for fear of waste or because we don't want to fight about it. Then their taste buds become more and more assimilated to bland, starchy foods and salty/sweet junk. So that's what we give them because battling for anything else is too exhausting.

We tell ourselves, "Kids won't eat that."

This scene from Anthony Bourdain's show in Lyon in which a bunch of rowdy children eat made-from-scratch butternut squash soup for school lunch proves otherwise. It also makes me cry with jealousy.

(I try to comfort myself with the fact that Bourdain himself said in an interview afterward, "This is a very sophisticated meal for children. I was a little s**t in school, frankly, and like a lot of the other students, I wanted pizza, pizza, pizza.”)

Don't get me wrong…France has plenty of crap food. But as a society, they seem to expect children will eat like adults come mealtimes, and most adults consume plenty of whole foods.

And it's not just France that expects kids to eat more varied diets. This seems common in any community that values cooking from scratch and refuses to make separate “kid” meals. I just happen to live in a place where that's not always the norm.

For a while, I took it all in stride. I ate plenty of processed foods as a kid and have vivid memories of seeing how many Oreos I could stuff in my mouth at a time. But my mom and many of the other parents around me balanced that with healthier whole foods.

So, with school lunch, my daughter and I compromised. She could buy her lunch once a week, and I'd pack her lunch the other days.

It's going to be fine, I told myself with deep breaths.

Then, the lunches I packed started getting rejected. "No one has cooked food like that!"

I switched to sandwiches, trying different combinations: Cheddar with mustard and lettuce. Ham with pickles. Always with fruits and vegetables on the side.

Bread then became an issue. For health and flavor, I like seedy, whole-grain breads. "I don't want to be the weird healthy kid anymore!" she told me.

I tried sourdough white breads, thinking they at least seem to be better on the digestive system and naturally have a long shelf life. Denied.

When I let her pick out her own bread, she opted for sweet and puffy sliced brioche or the kind of squishy white bread you can press into a bouncy ball.

Instead of the freshly sliced cheddar I normally bought, she wanted plasticky American cheese.

I tried homemade versions of "Lunchables" with cheeses and charcuterie I sliced myself as well as some raw vegetables.

No, no, no.

The lovingly sliced carrots from a local farm were rejected in favor of bagged, wet carrot nubs. She told me she preferred the supermarket Red Delicious to the heirloom variety apples I'd get from a nearby orchard.

What happened to the mantra, local food tastes better?

Breakfast then turned into a battle. For a while, we got along with some mix of unsweetened yogurt and granola or fruit with oatmeal or crispy eggs with toast or smoothies.

All fine.

Now, she only wants store-bought bagels and cream cheese or Pepperidge Farm Cinnamon Bread. (For my own mental health, I don't look too closely to find out what keeps the bagels soft and bouncy without molding for weeks.)

She recently told me that she now also wants bagels for lunch, with American cheese and mayo.

"Isn't that basically what you had for breakfast?" I asked.

"But at lunch, it has mayo," she told me. I kid you not.

Why does no one else seem to care?

Sometimes, I get a little panicky about all the junk my daughter eats so I'll push back when someone offers her candy at the pool after a day she's eaten little but cookies, hot dogs, chips, and blue popsicles.

If I say no in public, people, including some fellow parents, will treat me like I'm a fussy killjoy who can't just lighten up and let her kid have "a little treat." (Never mind that her entire diet has consisted of "little treats" with no fresh food all day.)

Completely overwhelmed with the systems that make industrial processed food so cheap, convenient, and easy-to-like, it seems like we've all collectively shrugged. We tell ourselves it's no big deal as diseases like Type 2 diabetes rise and the growing body of research that shows the connection between our gut microbiome and mental and physical health.

People have told me, “She's so active, don't worry about it.”

My concern has nothing to do with weight or calories and everything to do with nutrition and enjoyment of foods that aren't industrially processed. I also stress about the fact that the nutrient density of our food supply has gone down significantly since the turn of the twentieth century. Not to mention the climate and cruelty implications of our industrialized food systems.

Meanwhile, my daughter and I enjoy the satirical account @reallyverycrunchy on Instagram. I don't know much about the woman behind it, but part of the genius of her videos is that she both supports “crunchy” philosophies (like eating whole foods, avoiding “toxins” and reducing the use of plastic) while making fun of the anxiety and judgment they provoke.

They remind me that, actually, some people really do care. They care so much about giving their kids the foods that are best for their bodies and the environment that it's hilarious and a little weird. And when you care that much, you're viewed as uptight, preachy, and no fun at all.

The fact that it's funny also indicts the larger culture that's telling the crunchy moms to chill out and let your kid have the Gatorade already!

One day, my daughter said to me, “I'm so glad you're not a crunchy mom.”

“I tried to be one…,” I said weakly.

Now, I know my family is so privileged to be able to pay for the foods we want to eat and have access to many wonderful ingredients. But this only fuels my frustration.

If I can't figure this out as a cookbook author who lives within fifteen minutes from organic vegetable farms and has the time and inclination to cook, who can?

I'm sure my anxiety about her pickiness only makes it worse, and yet, I also know that if I don't resist, she'll eat nothing more than refined starch and cheese for every meal: boxed mac & cheese, pizza, quesadillas, ravioli, grilled cheese, cheeseburgers, nachos, Doritos, Cheetos, and, of course, the bagels.

Then she'll follow that up with some candy and anything made with blue dye no. 1.

Look, I know: Cheesy, starchy foods are delicious foods and have their place. I enjoy them, too. And I understand there are many ways to eat healthfully. But you don't have to be a trained medical professional to know that a diet full of highly processed grains, dairy, and sugar is…not ideal.

What about dinner?

Dinner, for now, is still mine. I cook what I want, and she's gotta eat it. But her growing visible and audible displeasure with my food grates on me.

Earlier this year, I cycled through the same few dinners, too drained to try harder.

But lately, I’ve been trying again, cooking based on what inspires me, and recording the meals that are most successful.

Glimmers of hope

So much advice is geared toward the littlest ones, and I feel like no one tells you how challenging it can be when they're older.

While I feel like most of my younger mom optimism has been steamrolled by our standard American food culture, I have found glimmers of hope.

For example, when my daughter comes with me to friends' houses, she eats what they serve without protesting. Even if she tells me later that she only liked the blandest, starchiest thing on the table, she exposed her tastebuds to something new. In the long run, I know that will make a difference.

Plus, some of her friends love the food I cook. I love these friends and their positive peer pressure.

Now that we feel comfortable going to restaurants again, I make adventures around trying new places, especially those that don't serve the burger/chicken finger/pasta trilogy. Have a lacrosse game 30 minutes away? Let's drive out there early to try the Korean restaurant nearby for lunch.

I've also started experimenting with a homeschooling technique called "strewing." Every few days, I'll leave out a new cookbook or two within her line of sight, hoping her natural curiosity will encourage her to leaf through it. So far, it's worked when the books are geared toward kids or they have something sweet on the cover.

Inspired by a book, she'll sometimes get into the kitchen to make something. Whether or not she follows the directions is a whole other story, but I love that she's starting to be open to cooking.

In the end, as parents, we have less control than we think we do over our children’s eating habits, especially when our food ideals go against the culture’s predilections. But I also take heart in the fact that picky kids don’t always become picky adults.

For my friends struggling with picky eaters of any age, let me borrow some words from Crunchy Mom, “You got this, mama! (And papa!)”